With over 1500 species in Staffordshire (out of 2500 in the UK), the butterflies and moths form a important part of our insect fauna. The butterflies are one of the best known groups of insects, familiar to all yet, with less than 40 species being seen regularly, they form only a very small part of the Lepidoptera of the county. However, until recently, they have received the most attention, mainly because they fly during the day whereas most moths are nocturnal and there are many more books on the identification of butterflies than there are on moths.

In the last 10 years we have seen the publication of new field guides to the moths, illustrating them in their resting position rather than as dead specimens in display cases. Together with the advent of the digital camera and the proliferation of on-line sources they have revolutionised an interest in these fantastic and beautiful creatures. We hope that these pages will enable you to learn more about the Lepidoptera of our county and to contribute, via your records, to our further understanding of them.

This atlas of the Moths and Butterflies of Staffordshire is based upon The Larger Moths of Staffordshire[1] and Atlas of Lepidoptera of Staffordshire; Part 1 Butterflies[2], but now includes more detailed maps of all the moths (macros and micros) and butterflies too.

| NSJFS | North Staffordshire Journal of Field Studies, published by Keele University (1961-1981) | |

| TNSFC | Transactions of the North Staffordshire Field Club (1866-2002) | |

| VCH | Victoria County History edited by W.Page (1908), download the text from The Internet Achive |

A number of records have not been accepted for the atlas, these are listed here

In order to maintain continuity of recording area and to help put historical records in to context, we have adopted the boundary of Staffordshire as it was in 1852 (the vice-county of Staffordshire[1]) and as it was prior to the changes of 1974. It thus includes some areas, such as Sandwell Valley, that are no longer within the present county boundary. There is even an outpost of Staffordshire in the Wyre Forest!

Staffordshire measures, at the extremities, some 56 miles (90km) north to south by 38 miles (60km) east to west and ranges in height up to 1,684ft (513m).

The county can be divided into three distinct physical regions: the northern hills, the central plain and the southern plateau.

The hills in the north-east, which reach 1,684ft (513m) at Oliver’s Hill, comprise an extensive area of moorland and represent the southern tip of the Pennine Chain. They are composed of Carboniferous grits, shales and limestones.

To the south and west we find an area of hill country between 400ft (122m) and 800ft (244m) which is dissected by a series of rivers that flow NW to SE into the Dove and Trent.

The central plain, composed largely of Triassic marls, is a low-lying area of land drained by the River Trent which rises near Knypersley Pool and flows eastward towards Stafford and thence to Burton-on-Trent.

The Southern Plateau, comprising Triassic sandstones and pebble beds and Coal Measures, rises to 800ft (244m) on Cannock Chase; an important site for lowland heath. On its western flank the River Penk flows north to join the River Sow near Stafford while to the east the River Tame flows north to join the Trent. There are also a couple of limestone inliers, notably around Wren’s Nest near Dudley.

The county thus encompasses a wide range of habitat types including limestone dales, gritstone moors, acid heaths and bogs, deciduous and coniferous woodland, upland and lowland water bodies, and even a small patch of saltmarsh!

Given its central position, the county is also home to species that are at either the northern or southern limits of their ranges.

The scope for the lepidopterist is indeed extensive.

From a recorder’s point of view the county covers all of twenty full 10km squares with another 19 being partly in another county; 662 (+226 in part) tetrads (2x2km) or 2,806 (+482 in part) 1km squares of the National Grid. Unlike birdwatchers and botanists, lepidopterists are thin on the ground and so the distribution on anything finer than a 10km grid is partly a map of the distribution of lepidopterists for some of the less common species. Nevertheless, the maps do show if a species is widespread or local, northern or southern, eastern or western, whether it is declining or expanding, and where the gaps in our knowledge are. As more records are received then we will be able to refine the maps.

Basically, ANY data is welcome! Entomologists are so thin on the ground that records of invertebrates generally are much sought after. It is therefore vitally important that any records are passed on to the County Recorder and Staffordshire Ecological Record.

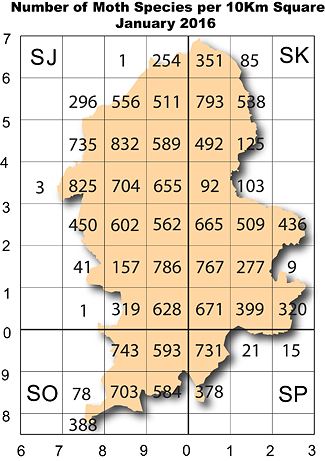

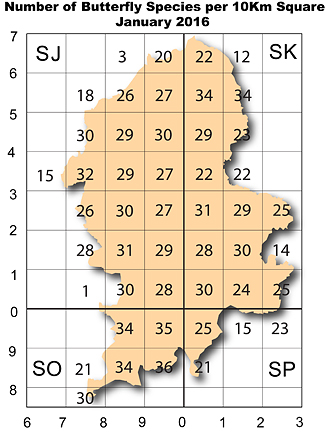

No matter where you record, the chances are that you will either add new species to the 10km square list or update existing records. The map opposite shows the number of species of butterflies and moths recorded in each 10km square.

There are some squares such as SJ81, SK03, and SK14, for example, that are obviously under-recorded. However, it must be realised that the records for the well-recorded squares are often based on just a single locality i.e. one site within 100 square kilometres! If we are to produce more refined distribution maps then we at least need data from each tetrad (2 X 2km).

It should not be necessary to point out that you must obtain the landowner’s permission before visiting a site but it is worth mentioning that you should inform neighbouring properties and the police if you intend to run a moth trap. After all, a group of people sitting around a lamp in the dark is going to raise the suspicions of the un-initiated!!

Finally, just to reiterate, even if you only record from your garden, the data is useful – please send it in.

Records of all Butterflies and Moths can be sent direct to Dave Emley, County Moth Recorder or c/o Staffordshire Ecological Record

They can be submitted in any format but for large numbers of records computer files would be especially welcome. If you can submit them as a spreadsheet (excel) or as comma (CSV) or tab-delimited text files then so much the better. If you are unsure about file formats then please contact me. Whatever method you choose please include the Bradley checklist code number (these are also given in all the field guides), species name, locality, grid reference, date and name of recorder. A suitable minimal spreadsheet layout would be:

| Code | Species Name | Site | Grid ref | Recorder | Quantity | Date |

|---|

You could add a comments column if you like.

Alternatively, if you are recording from just one site e.g. your garden a more convenient format for inputting records is:

| Species name | code | 10/06/2010 | 11/06/2010 | 12/06/2010 | 13/06/2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood-vein | 1682 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

and then just fill in the totals; one row per species. I have written some code which will turn this format into one which MapMate can import.

Basically, as long as you are consistent in the way you send in your records, I can write a conversion programme to handle the data.

Photographs and digital images can be sent to Dave Emley for confirmation.

MapMate is becoming the standard storage software for lepidoptera and other orders. However, please export your records as an excel or tab-delimited file before sending them in. There are user queries in MapMate to do that.

Interest in butterflies has always been strong but interest in moths has increased dramatically following the publication of Waring’s[1] and Skinner’s[2] books. The quality of the illustrations is such that many newcomers no longer feel the need to kill specimens for reference, opting sometimes for photographs instead. Whilst this attitude is to be applauded, it must be realised that it is not always possible to identify a moth by comparing it to an illustration. For example, there are a number of species (especially those with melanic varieties) that cannot always be identified without recourse to dissection of the genitalia. There are also rare species that look very similar to much commoner species. In such cases either dissection or comparison with a series of mounted specimens is then necessary to aid identification. In addition, moths, unlike birds and plants, can exhibit so much variation that two members of the same species can, in the extreme, look like quite different species. This range of variation cannot possibly be fully covered in books.

Identification of butterflies is generally straightforward but to help you decide if a moth record needs some sort of confirmation, there are a couple of downloads which give an abundance code to each species ranging from 1 for very common, to 4 for rare and requiring confirmation.

So, before submitting a record of a rarity, ask yourself a few questions:

Problems such as those outlined above make the vetting of records not supported by voucher specimens, problematical. It is vital that workers in the future should be able to rely on the data that we provide so the following procedure will be adopted:

he Staffordshire Moth Group is devoted to the study, recording and, above all, enjoyment of moths and butterflies in the vice-county of Staffordshire. Much of the information used to produce the maps in this atlas is based on the work of members of this Group.

If you are new to moths then you might find the Getting Started (Moths) section of use. If you are a seasoned moth hunter then the distribution maps might spur you on to greater things!

Dave Emley – County Moth Recorder.

The only way to learn is to meet other people. The Staffordshire Moth Group’s electronic newsgroup has been set up for this purpose. If you are holding a mothing evening then advertise it on the E-group. Likewise, if you have a problem moth then why not post a photo to the E-group.

The E-group is set up under Yahoo and membership is by invitation only. That we we can reduce the amount of spam. If you join the group then you can elect to receive messages by email or you can visit the Yahoo Group site and read them there. There is a full archive of past messages. There is also space for uploading photos and files too.

If you are interested in joining then contact Dave Emley – County Moth recorder.

| County Moth Recorder | Staffordshire Ecological Record |

|---|---|

| Dave Emley William Smith Building Keele University Keele Staffordshire ST5 5BG Tel (9am-5pm) : 01782 733617 email: recorder@staffsmoths.org.uk | Craig Slawson Ecological Records Officer Staffordshire Ecological Record, The Wolseley Centre Wolseley Bridge Stafford. ST17 0WT Tel: 01889 880100 Fax: 01889 880101 E-mail: info@staffs-ecology.org.uk |

| Potteries Museum and Art Gallery | Staffordshire Wildlife Trust |

| Natural History Unit Bethesda Street Hanley Stoke-on-Trent ST1 3DW Tel: 01782 232323 Fax: 01782 232500 Email : museums@stoke.gov.uk | The Wolseley Centre Wolseley Bridge Stafford ST17 0WT Tel: 01889 880100 Fax: 01889 880101 Email: info@staffs-wildlife.org.uk |

So, you’ve probably been to a mothing session and seen all those interesting, and quite pretty, moths or you’ve seen Bill Oddie running around with a net on the telly and you are hooked. You may have brought a light trap or just seen moths on your window or feeding on your buddleia but, there’s no one around to tell you what they are – help!!!

For anyone getting interested in moths for the first time it can be very confusing! With over 2400 species where does one start? I have to say that one doesn’t start in mid-summer when most species and numbers occur. And, unlike birds and plants, the same species of moth can exist in a number of, sometimes many, different coloured forms, adding to the confusion. What can you do?

Just joining a moth group is half the battle. There is no substitute for going out with others. Also, visiting your local museum and looking through their collections will help. A very useful article can be found on Jon Clifton’s Anglian Lepidopterist Supplies site.

As with all hobbies it is possible to get bogged down in a spiral of expense but that need not be the case. As a minimum you will need a good field guide, a net and some clear plastic tubes or boxes. You may also want to buy or construct a light trap. As you progress you will find that you are catching moths not in your field guide or which you can’t identify. Then, a digital camera will enable you to send photos to others – possibly via our E-group – for identification or confirmation.

There is plenty of information on mothing out there on the web and the number of books on the subject is increasing. The notes on the related pages will guide you in the right direction and hopefully start you on the road to a lifetime’s enjoyment of moths.

[Collapse]

Firstly, how do you know that you have a moth at all – there are a few insects that could be confused with them! Moths, like butterflies, are members of the Lepidoptera, the majority of which are characterised by the possession of a coiled proboscis and a body covered in minute plate-like scales.

Many moths are day-flying and could be confused with butterflies. Butterflies have a clubbed antennae and moths have a variety of different-shaped antennae but only the Burnets have one resembling a club.

The nearest insect group with which they could be confused are the Caddisflies. However, their bodies are covered in hairs and their antennae are always held out in front of them in a characteristic manner as in the photo on the left.

Historically the moths have been split, rather crudely, into two groups – the microlepidoptera (micros) and the macrolepidoptera (macros) – the latter also being known as the Larger Moths. Of the two groups the micros are by far the most numerous with many species being only a few millimetres in size. In contrast the macros are generally much larger and comprise those insects that people generally associate with the term “moth”. Micros, because of their small size, lack of available illustrations and general difficulty in identification, have never been as popular with naturalists as have the macros. As to whether a moth belongs to one or the other group is an interesting question, for some micros are larger than some macros and vice versa. Suffice it to say that the macrolepidoptera or larger moths comprise all those species covered and illustrated by both Waring and Skinner.

[Collapse]

Although the majority of larger moths are nocturnal, there are a number of day-flying species and it is with these that most people will be familiar. They include, for example, the blue-and-red burnets and Cinnabar moth (left), the black Chimney-sweeper, and the yellow-and-black Speckled Yellow, as well as familiar migrants such as the Hummingbird Hawk-moth and the Silver Y. They may be looked for in the same places that you would expect to find butterflies e.g. flower-rich meadows, waste ground, embankments etc.

The majority of species rest during the day and, to avoid being detected, have become masters of disguise. Some will rest up amongst foliage, leaf litter, grasses etc. from where they may be disturbed when walking past or they may be actively dislodged by tapping the branches of a tree or bush. Many will rest on tree trunks, fence posts, boulders etc. and, as you would expect, can be very difficult to detect. However it is worth persisting because one soon “gets one’s eye in”.

Moths, like butterflies, are attracted to flowers. It is therefore worth checking the plants that the butterflies were feeding on during the day; but at night. You may well be surprised at the numbers of individuals and species on your Buddleia, for example. In the spring, sallow catkins are well worth looking at too.

Many moths have familiar caterpillars but many more have rather nondescript larvae or, in some cases, the larvae have never been found in the wild at all. The publication of Porter’s book; Caterpillars of the British Isles, means that we now have a ready source of reference for identification. Nevertheless, many caterpillars can only be safely identified by rearing them through to the adult – and there is plenty of literature on this subject; for example Dickson’s Lepidopterist’s Handbook.

The larvae of a number of the smaller moths feed between the upper and lower surfaces of a leaf, excavating distinctive trails or mines. The shape of these mines, coupled with the plant on which they are on, can be used to identify the species that made them. In many case the mined leaves can be kept and the adult moths reared. It is a rather specialised field but is often the only way to get records for the species concerned. There is a website dedicated to their study.

[Collapse]

Even employing all the methods discussed under “searching”, only a fraction of the moths of an area will be found. We need to make the moths come to us and there are several ways we can do this.

Moth hunters have traditionally used a method called “sugaring” to attract moths. This is very simple and can be employed to good effect in the garden. It involves preparing a sweet-tasting concoction, painting this on tree trunks, fence posts etc. and visiting these patches at intervals throughout the night. Every moth hunter has his or her own recipe for the mixture e.g. black treacle and molasses, but I have found that golden syrup with added sugar and a touch of alcohol (!) works quite well. The moths become almost drunk on the mixture and can then be approached quite closely as you can see with the Buff Arches opposite.

A method that is increasingly being used involves soaking lengths of cord in cheap red wine to which sugar is added and draping these wine ropes over vegetation. They are really another type of “sugaring”.

The females of a number of species of moth emit a chemical scent or pheromone to attract males. In days gone by one of the methods of finding moths like the Emperor was to place a reared female in a muslin cage on the heather and wait for the males to be attracted. So powerful is this attraction they would come to an empty cage that recently contained a female.

It is now possible to purchase artificially produce pheromones for a number of species and these are being very successfully used in the county to attract Clearwing moths – traditionally a very difficult family to study. Anglian Lepidopterist Supplies are a good source of these and an article on their use appears in our 2005 newsletter.

[Collapse]

It is a well-known fact that moths are attracted to light – be it a small flame or a bright bulb – and we can employ this attraction to great effect. Almost any source of light will do but there are two considerations.

Firstly, the ultra-violet (UV) content of the light source is important as moths are particularly sensitive to this region of the spectrum. Secondly, the attraction to the light is stronger if it is the sole source of illumination i.e. there is a good contrast between the light source and its background. For example, a solitary white street lamp (the orange ones are no good) in a dark country lane will be more attractive than one in a well-lit urban area.

However, it is worth noting that not all species are equally attracted to light and, with some, there is even a difference in attraction between the sexes too. It is important to realise, therefore, that a moth trap will not necessarily give a complete list of the species inhabiting a given area so one needs to employ a range of survey techniques. That said, let us briefly consider some of the ways in which we can use light to attract moths.

The simplest source of light is an illuminated window. Moths will often sit on the window or on the adjacent wall. Alternatively, if you have a security light that stays on then it is worth checking the surrounding area at night and first thing in the morning. Campsite toilet blocks with their outside lights and white-washed walls are renowned for attracting moths!

Before the advent of modern moth traps, the traditional way of attracting moths, especially in the field, was to use a spirit lamp such as a Tilley Lamp. Today, a butane gas lamp would do just as well. This is still a good method and to make it more effective, the lamp can be suspended in front of a vertical white sheet. The moths will then rest on the sheet where they can be examined.

By far the most effective method is to use a moth trap. The basic principal is to mount a light source within a funnel situated on top of a closed box lined with egg cartons. The moths are attracted to the light and fall through the funnel into the box. Here they hide amongst the egg cartons quite happily until the morning when the catch is examined and the moths released – well away from any waiting birds!

The best light source is a mercury vapour (MV) lamp – as used in the white street lights mentioned earlier. The problem with these is that they require a 240 volt supply and the bulbs become very hot and need to be protected from the rain. However, these lamps can, in some circumstances, attract vast numbers of moths in a night. They also emit UV so it is important to take sensible precautions, and not to look at the bulb directly. The Skinner trap, illustrated left, is a common moth trap of this type. It can be used in the field but requires a portable generator or access to a mains supply.

An alternative is to use the blue fluorescent lamps that are incorporated into the insect killers that you see in butcher’s shops and bakeries. It’s not the bulb that kills the insects but a wire grill in front of it. These tubes, known as Actinic tubes, emit quite a lot of UV but they are not as bright as the MV lamps. The advantage of them is that they will run off a normal 12 volt car or motorbike battery as well as off the mains. This means that they are portable! They also will not disturb the neighbours! On any one night they will not attract the numbers of moths that a MV lamp would but, over a period, they will eventually attract the same species. Such a trap – known as a Heath trap – is illustrated right.

Note, however, that not all the moths attracted to the light will end up in the trap. It is common for moths to dive for the shadows or to land on the ground around the trap rather than fly straight to the bulb. To overcome this, the trap can be placed on a white sheet and the moths examined as they land. From personal experience I have also found that the Skinner-type trap attracts fewer geometer or “carpet-type” moths than the Heath trap.

Be warned; moth trapping can become addictive! There is always a sense of excitement when emptying the trap for you never know what is going to be inside. Most of the time the moths are fairly predictable but now and again there is always a surprise, especially when trapping in a new area. Moth trapping provides hours of harmless fun while at the same time providing valuable data.

[Collapse]

Moths can be found in any month of the year. The graph of the number of species per month in Staffordshire shows that the peak is from June to August. For someone taking an interest for the first time, the sight of a trap full of moths in, say, July can be quite daunting. It is better to start off in the spring or late autumn when numbers are more manageable.

Not all nights are equally good for moths. For example, a warm sunny day with a cloudless sky might be good for butterflies and day-flying moths but it is generally followed by a cold evening when few moths will fly.

The best nights tend to be cloudy, mild, and preferably muggy. Unfortunately we tend to get too few of these!

Moths do not fly throughout the night but have definite periods and peaks of activity. Some species fly only at dusk for instance, when there is usually quite a lot of activity. Peak numbers probably occur shortly after dusk and then tail off until renewed activity starts at dawn.

[Collapse]

Grey Mountain Carpet

Foxglove Pug

Clouded Magpie

Barred Red

Moths can be found in every corner of the county but, if you look at the distribution maps, you will see that some species are found throughout the county whereas others occur in only one or two squares. Why a certain species occurs where it does can be an intriguing question. The answer is partly tied up with the availability and distribution of its foodplant, but that is not the entire answer.

Take the Grey Mountain Carpet for example. It feeds on heather; a not uncommon plant in the county. However, the heather must be growing above 300m so that restricts the available habitat to the heather moorland in the far north. We are, in fact, at the southern limit of its range. In contrast, the Foxglove Pug feeds only on foxglove and, as that is a widespread plant, so too is the moth.

Being restricted to a single foodplant can have its disadvantages. The Clouded Magpie and the Dusky-lemon Sallow both feed on elms – a tree that was not uncommon in the past. However, since the Dutch elm disease wiped out most of our elms, the moths have become much scarcer and, in the extreme, could disappear altogether.

Some distributions are harder to explain. Why, for example, does the Scorched Carpet, which feeds on spindle, occur at sites where spindle has not been found? The Juniper Pug feeds, not surprisingly, on juniper. However, Staffordshire Flora shows that wild juniper does not occur in the county, yet the moth is quite widespread. The answer, of course, is that the species has taken to feeding on garden cultivars and it is we who have aided its spread through the county. The same can be said of the Juniper Carpet, Freyer’s Pug and Blair’s Shoulder-knot.

Many species are found all over the county and these are usually non-specialist moths, feeding on a wide variety of common plants or “weeds”. Others, like the Grey Mountain Carpet mentioned earlier, feed on common plants but only in certain habitats. The Bulrush Wainscot feeds in the stems of reed mace and, as this plant is found in marshy areas and reed beds, so too is the moth. Likewise, the Barred Red, Pine Carpet and Spruce Carpet feed on conifers and so are usually found in and around pine woods.This restriction to habitat and foodplant can be of use when you are puzzling over the identification of a new or rare species of moth. If you are not sure of your identification, ask yourself if the habitat and foodplant availability are right for the species in question before claiming it.

[Collapse]

Let’s be honest, you are going to be confused when you first start. Even if you start in the early spring when the number of species is low, it may take you several hours to go through 50/60 moths. However, you soon get to know the commoner ones. You will need to buy at least Paul Waring’s book and probably Bernard Skinner’s too. Be warned though; these only cover the macros and some micros are as large, if not larger than some macros! Luckily there is now a field guide by Sterling covering a large proportion of those too.

OK, you’ve got the books and everything in the trap is not in your book and so must be new to science! We’ve all been there so don’t get downhearted. Even if you only identify one or two; that’s one or two less to identify the next night. Soon you will have recognised all the common species flying at the time and you will be able to concentrate on the new ones.

This isn’t the place to go into details about identification but here are a few pointers:

Having identified your catch what next? How do you know you’ve got the identifications right? Any moth-er will tell you that you can get it horribly wrong when you first start – even when you’ve been at it for time too!

Don’t worry if you struggle at first – we all did – just enjoy it. It’s not worth doing it otherwise.

[Collapse]

So, you’ve identified all your moths and have accumulated a lot of records. What do you do now. Well, you don’t have to do anything. You could keep all the data to yourself. However, data on insects is in short supply and any records, even those from your garden, are valuable. We amateurs are in a unique position to contribute to our knowledge of the natural world and it is vital that we all add to this knowledge by pooling our records. The maps that you have seen on this web site and in the Moth Atlas have all come from folks like ourselves.

The County Moth Recorder coordinates all the records of moths in the county, so all records should be sent to him in the first place. He will look through them and may get back to you with queries on some of the rare species and may ask you if you are sure of the ID. Don’t be alarmed by this; it applies to everyone – even seasoned moth-hunters. It is vital that only correct identifications are stored on the database. Future workers have to be able to rely on the accuracy of past records.

Having accepted your records he will enter them on the county database and also forward a copy to the Staffordshire Ecological Record who are the central county database for all species.

To attract butterflies to your garden you need to provide nectar for the adults but it is just as important that there is food for the caterpillars, either in the garden or close by.

Many butterflies have very strict habitat requirements and it is not possible to duplicate these conditions in an average garden so, unless your garden adjoins such a habitat you are unlikely to see these species. The ones that we do see are very wide-ranging and generally feed on common plant species.

To attract butterflies into your garden you need to grow a selection of plants that will provide nectar from spring right through to the autumn. Choose a sunny, sheltered spot, ideally it should be south or south-west facing. Also, it is important to plant a number of each species to make a visible display and one that will give off a strong enough scent to attract the butterflies. Remember that single-flowered plants are best as the nectar in double flowers is inaccessible.

When deciding on what to plant it’s a good idea to have a look at what the butterflies are feeding on in the wild in your area and then select something similar from the list below.

Don’t forget that whatever you plant for butterflies will also attract moths; you will just have to go and look for them with a torch!

| Annuals and Biennials African marigold Tagetes erecta Ageratum Ageratum houstonianum Alyssum Lobularia maritima Candytuft Iberis amara Cornflower Centaurea cyanus French marigold Tagetes patula Heliotrope Heliotropium cultivars Honesty Lunaria annua Marigold Calendula officinalis Stocks Matthiola incana and hybrids Sweet William Dianthus barbatus Verbena Verbena rigida Wallflower Erysimum cheiri Herbaceous Perennials Alyssum Aurinia saxatilis Arabis Arabis alpina Astrantia Astrantia major Aubrieta Aubrieta deltoidea Candytuft Iberis sempervirens Catmint Nepeta× faassenii Dahlias – single flowered types Elephant’s ears Bergenia spp. Forget-me-not Myosotis spp. Globe Artichoke Cynara cardunculus Globe Thistles Echinops spp. Golden-rod Solidago spp. Hyssop Hyssopus officinalisIce Plant Sedum spectabile paler varieties are better Jacob’s Ladder Polemonium caeruleum Michaelmas Daisy Aster novae-angliae Mint Mentha spicata Phlox Phlox paniculata Red Valerian Centranthus ruber Scabious Scabiosa spp. Sea Holly Eryngium spp. Soapwort Saponaria spp. Sweet Rocket (Dame’s Violet) Hesperis matronalis Thrift Armeria spp. Thyme Thymus spp. Verbena Verbena bonariensis Shrubs Blackberry Rubus fruticosus Butterfly Bush Buddleja davidii, also B. globosa Cherry Laurel Prunus laurocerasus Escallonia hybrids Firethorn Pyracantha Hawthorn Crataegus monogyna Heather Calluna vulgaris Heaths Erica spp.Hebe spp. Ivy Hedera helix Japanese Spiraea Spiraea japonica Lavender Lavandula spp. Oregon Grape Mahonia aquifolium Privet Ligustrum spp. Sallows Salix spp. Native Wild Flowers Angelica Angelica sylvestris Bugle Ajuga reptans Buttercups Ranunculus spp. Clovers Trifolium spp. Dandelion Taraxacum officinale Fleabane Pulicaria dysenterica Garlic Mustard Alliaria petiolata Hawkweeds Hieracium spp. Hemp Agrimony Eupatorium cannabinum Knapweeds Centaurea spp. Lady’s Smock Cardamine pratensis Marjoram Origanum vulgare Purple Loosestrife Lythrum salicaria Sallows Salix spp. Scabious Knautia arvensis and Succisa pratensis Stonecrop Sedum acre Teasel Dipsacus fullonum Thistles Cirsium spp. and Carduus spp. Valerian Valeriana officinalis Water mint Mentha aquatica |

Remember that without food plants for caterpillars to feed on there will be no butterflies to visit your flowers! The average garden is not really suitable for many butterflies to breed. Leaving one or two nettles is not enough to tempt a Small Tortoiseshell to lay eggs – she needs large patches. So, it is important to make sure we have large areas of nettles, thistles, etc. nearby. Popular food plants include holly, ivy, cabbage, nasturtium, honesty, grasses, cuckooflower, blackthorn which may encourage species like the whites, Orange-tip, Holly Blue and Speckled Wood to breed.

The Smaller Moths of Staffordshire – updated and revised edition

by Dave W. Emley, 2014

ISBN 978-1-910434-00-0

The Smaller Moths, or Micro-lepidoptera, constitute the larger part of our Lepidoptera yet, because of their small size and lack of illustrative material, they have often been ignored. The first edition of this booklet by Richard Warren was one of the first local faunas to cover the “micros”. It is 25 years since it was produced and, following the introduction of several illustrative guides and handbooks, and the advent of the digital camera, interest in micros has boomed resulting in 143 species being added to the County list. Some of these are now widespread, yet were unknown to Richard!

This current work brings us up-to-date. It has no maps as these are readily available on-line but it gives an indication of their distribution by quoting the number of 10km squares recorded since 2000. It also indicates to the recorder how common or otherwise the species is.

Coverage of micros continues to be patchy but it is hoped that this new list will encourage further recording of these fascinating creatures.

Butterfly Conservation have produced a excellent series of factsheets containing essential information to enable the practical conservation of the butterflies and moths listed as Priority Species in the UK Biodiversity Action Plan, covering those species that breed partly or wholly on agricultural land. They are available as downloads by clicking on the relevant species name in the list.